Back in February of last year, I started to play around with using Microsoft Forms, mostly for knowledge quizzes and basic recap of material covered in lessons. I had used it for a few homeworks and was quite happy with the results. It allowed me to identify at a glance any major misconceptions across the class as well as being largely self-marking.

And then lockdown happened and I started to rely on it more and more. And as I started to rely on it, I started to think more deeply about how to maximise its potential. I didn’t want it only to be a vehicle for knowledge quizzes, as beneficial as they can be, but also as a way to encourage more generative learning.

As I started to consider how best to use it, I identified the following core aims, partly to align with remote learning but also to tap into the generative learning I hoped to encourage:

- Students can complete any quiz or task multiple times and independently

- The same quiz could be used across multiple classes

- It could be set as homework and submitted digitally

- It would require zero marking as feedback would be built into it

- Allow students to generate more extended responses and practise writing

- Encourage self-assessment and evaluation, cultivating the student’s metacognitive awareness of their current performance

The first three are all inherent features of the service and so not something I needed to consider, but the latter three, especially the final two, did require tweaking and refinement. This post outlines the eventual outcome of my experiments, and how I now use Forms on a regular basis.

The Format of My Typical Forms Quiz

Using the GCSE English Literature Poetry Anthology, specifically Mother, Any Distance, as a case in point, here is how I typically use Forms, although this same format has been applied to other texts and year groups.

I often like to begin with a small section on basic plot details and biography, which will help me to assess at a glance if there are any fundamental misconceptions across the class. These will often, but not always, be MCQ.

I then move onto a more substantial section, looking at various key quotations from whatever text is being assessed. These tend to be fill in the gap activities of various kinds, with about 10 quotations being used. As retrival practice of this kind is embedded in normal classroom routine, I feel fairly confident students would approach this in much the same way that they would in class, that being from memory and without looking at notes. The fact the responses are sometimes close and sometimes even entirely wrong would seem to support this suspicion!

At this point in the quiz, everything has been completely self-marking, but I can still see at a glance using an overview page whether there are misconceptions and patterns of certain quotations being recalled incorrectly. I might feed any such incorrect instances of recall into future in-class retrival practice to provide added opportunity to revisit this.

However, it’s the next section of the quiz that I think is especially powerful, helping to fulfil my desire for students to be able to generate more sustained responses and for better self-assessment routines. I wanted to try to find a way for the quiz to be more generative and not just fill in the gap or MCQ, but still not necessarily require any feedback from me.

In order to do this, I supply various key quotations from the chosen text and ask them to analyse it in the manner we would have prepared in class. There is no ‘right’ answer awarded for this, but when students submit their response they’re provided with suggested ideas that they could have included, sometimes as a bullet point list and sometimes as an examplar paragraph. They’re asked to use this to help self-assess their own response: did I make similar points? Is there anything especially important that I missed out? Did I talk about the image in enough detail?

Here is an overview of the instructions at the start of this section of the quiz:

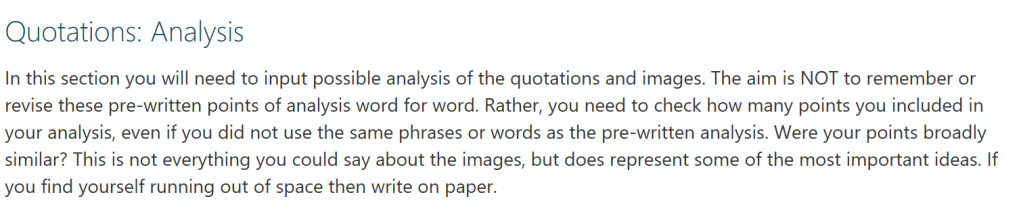

And here is the format that the questions take, as seen from the student’s perspective:

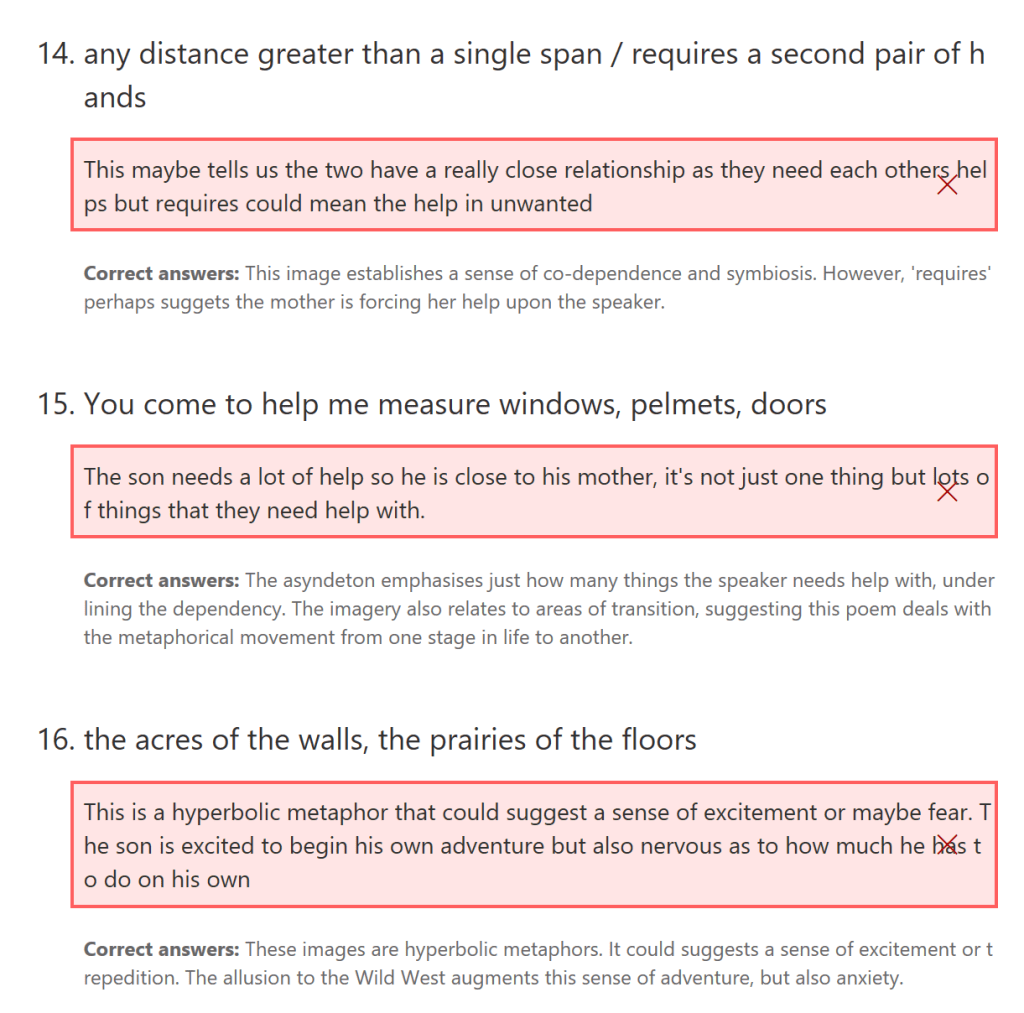

Once the students have inputted their answers and submitted the quiz, they are able to see the ‘correct’ responses, which includes the examplar material for this third section, as below:

The aim is not for them to learn this examplar response, but rather to use it as a concrete point of reference to better reflect on their own response. It is allowing open-ended analytical writing whilst still automating the feedback process. There is no essential need for me to comment on each response (although Forms does have this capacity), but they are still able to generate more sustained analysis, which is really valuable.

I’ve also recently become aware that the platform Carousel Learning allows something similar to this, as below, but with a couple of possible benefits over Forms:

- Encouraging students to self-assess and metacognitively reflect is built into the mechanics of the platform with the ‘Yes, I’m correct’ button, meaning, unlike Forms, students no longer see the big red X and they are being reminded to check against the model

- The student view is much cleaner, further encouraging better self-assessing routines

Carousel would certainly be something to explore further in this regard, and it does look promising.

Other Ways to Use Forms to Generate Learning

I’m a big fan of explicitly teaching and rehearsing how to write an introduction for the various texts I teach. Using the same principles as the above, I’ve designed a Form that includes structure prompts or a model example for the required text and then various different questions for the students to practise writing several introductions, using the model or prompt as a cue. The benefit to this is that it’s then really easy to read all at a glance and provide WCF as well as snipping good examples to discuss with the class.

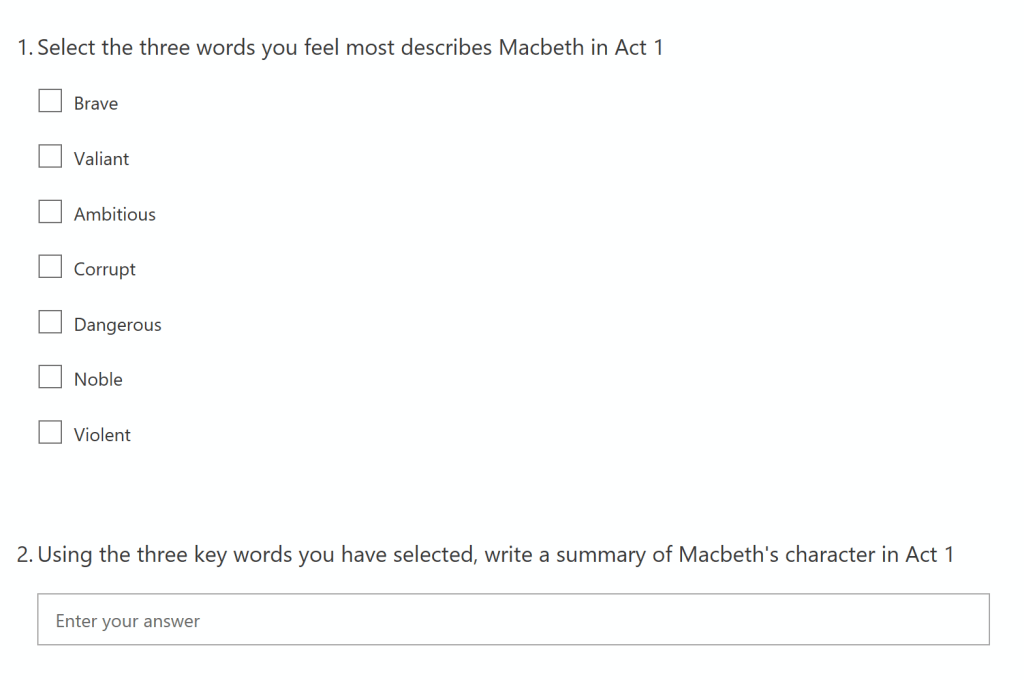

I also like the idea of using Forms as a way to organise and prompt effective summarising, which can be very useful if done well. Here, and after having modelled it, it is possible to break down the process of summarising even further. For example, as the first step, the Form might include a list of topics or words and students are encouraged to select the ones they feel are most relevant to the question at hand in the first instance, before then using those selected terms to write the summary. This helps to scaffold the process, provides the teacher with feedback as to how well students are selecting relevant information, and how that information is summarised.

Forms is also a really good way to better track and monitor any flipped learning tasks, with students being required to answer questions based on what they’ve been asked to watch or read. This could also feed into the above summary format as well as helping to assess misconceptions that can be addressed during the subsequent lesson.

And so, not just MCQs and knowledge quizzes, not, of course, that there’s anything wrong with those!